Last month, the Facebook page The Portuguese of Trinidad and Tobago shared a post detailing the twelve main contributions of the Portuguese to Trinidad and Tobago. The second contribution listed was “Rum and rum shops”. I began typing a comment suggesting that these be considered two separate but related contributions, but ultimately decided that the point was deserving of this blog post.

The contributions to Trinbagonian culture from various ethnic groups are often complex, connected, and almost impossible to properly quantify. For example, even in the previously mentioned list of twelve contributions, number nine was “Contributions to Calypso and Steelpan”, while number twelve was “Christmas Music”. Both are connected, but warrant being listed according to their own merit. Similarly, if one were to list the contributions of East Indian immigrants to the music of Carnival, the influence of Indian minstrels on the invention of Soca, and the evolution of Bhojpuri folk songs into Chutney would be seen as related, but separate contributions deserving of separate mentions. The same could be said about rum shops and rum being two related, but separate contributions of the Portuguese deserving of separate mentions.

The Portuguese Rum Shop

Many Portuguese immigrants came to Trinidad from Madeira, and they brought with them their knowledge of wine blending, connections to the old world that allowed them to source barrels for aging, and what has been described as what writer Jean de Boissière described as “their Latin love for a bodega”. These factors lead to a natural trajectory towards opening small groceries and becoming rum blenders. According to Doctor Jo-Anne Ferreira; “The Portuguese in Trinidad and Tobago typically opened rum-shops with adjacent groceries or dry goods shore, in some cases, or both.” She then says that “the early twentieth century witnessed the proliferation of rum-shops on almost every street corner of Port-of-Spain and indeed all over the country.” From here, the Portuguese rum shop became a Trinbagonian institution. The relevance of the Portuguese rum shop to Trinidad rum history could be seen in the importance of names like Black Label and Black Cat even today.

Beyond rum, these institutions allowed for the mixing of different social classes, and generations as well as the preservation of Caribbean cocktail culture. In the book And a Bottle of Rum by Wayne Curtis, a major theme is the importance of taverns and rum on American independence and the early political history of the United States. There is a similar parallel in the post- Independence politics of Trinidad and Tobago in which the rum shop plays a central part. Founding member of the People’s National Movement, Ferdie Ferreira worked in a Portuguese Rum Shop during his youth, and continued to use these institutions as a place to keep the party accountable and grounded via discussions and debates with other party leaders over drinks. Even in 2022, he still uses rum shop analogy, describing current politicians as a “watering down of the brandy” compared to the parliamentarians of yesteryear.

Politicians like George Weekes, John Humphry, and Basdeo Panday, who formed the first serious opposition to the People’s National Movement, shaped their political ideas in the rum shop. These three were of different races, and belonged to different social classes, but in the rum shop they were just three among many other patrons discussing politics and philosophy. The central theme of politicians in the rum shop is that it served as a place where elitist or radical political ideas were often forced to become more realistic.

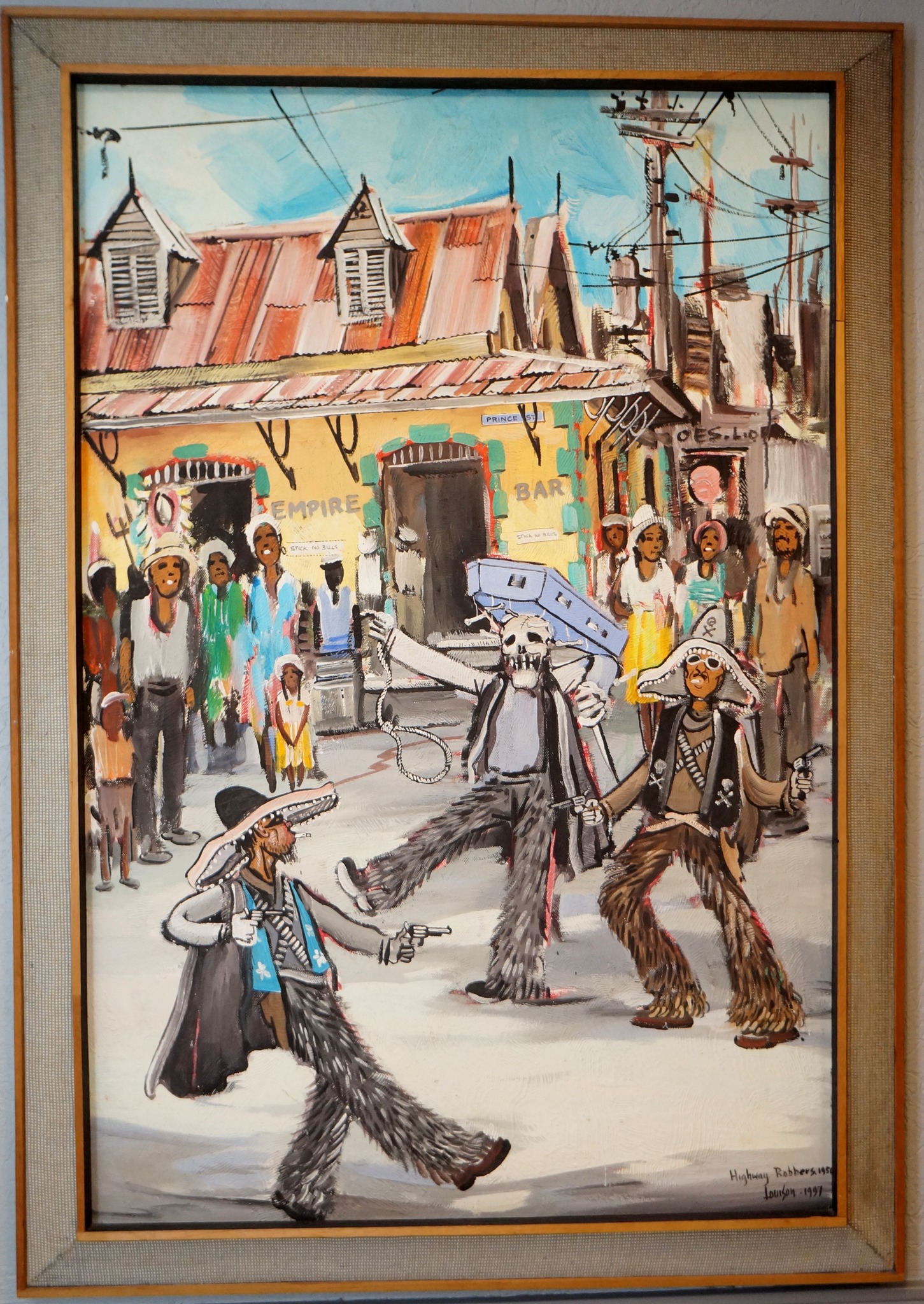

Beyond politics, the importance of the rum shop as a social hub extends into cultural events like carnival. Before the mass commercialization of this festival in recent times, band launches were hosted at rum shops, and many calypso, chutney, and soca songs were performed for the first time at rum shops. Beyond carnival, the rum shop also played a role in the promotion and preservation of lesser known subcultures all across the country. It is important to note here that the Portuguese were not the only ethnic group who owned and operated rum shops, but they were prominent enough that the trope of the Portuguese rum shop as the de facto community rum shop is rooted in reality. This means that the cultural and political importance of the rum shop in general automatically applies to the Portuguese Rum Shop.

The rum shop is a contribution of the Portuguese because of its influence on politics, culture, and cocktails. This contribution does not even include the rum, which is itself a separate contribution.

The Portuguese Creole Rum Style

It is now broadly accepted that the cultural contributions that lead to a particular style of Caribbean rum are deserving of recognition. For example, the rum of Jamaica and the rum of Martinique are stylistically distinct from the majority of rum produced and sold in the world today. Rum from Martinique has a grassy and herbal note due to the fact that it is made from fresh sugarcane juice fermented over a relatively short period of time. Rum from Jamaica on the other hand, is made from molasses that is fermented for a very long period of time and due to this, it has an intense character of ripe fruit. Descriptions of the development of these styles often include a reference to specific cultural events that lead to them, and the importance of recognizing and respecting the culture. Martinique Rhum Agricole, and Jamaican Overproof, the white rum associated with each style are often cited as examples that encompass the raw, untamed nature of each style. Additionally, the words Agricole and Overproof in those cases are taken beyond their literal meaning and are said to have a deeper cultural connotation. A parallel can be seen here with Puncheon rum. A style of white rum linked to Portuguese blenders in Trinidad, Guyana, and Antigua. If Agricole and Overproof are culturally significant white rums worthy of special mention, Puncheon is also deserving of a similar status.

Additionally, in recent times, the knowledge of the Cuban Rum Masters has been added to UNESCO’s list of Intangible Heritage. According to Matt Pietrek; “the real skill of the Cuban rum masters is their knowledge of blending multiple rums, as well as their masterful use of old barrels.” Essentially, it’s more than just knowing how to blend light rum and heavy rum, it’s also about understanding issues like barrel char, how often a barrel has been used in aging before, and even the effects of environmental factors like temperature and humidity. If such knowledge is worthy of being considered intangible heritage, then the knowledge of the Portuguese rum blenders who shaped Trinidad rum should be recognized for their cultural contribution.

In closure, other places in the Caribbean have all honored the cultures that lead to their unique rum styles, and the architecture of older rum shops are often preserved. Should Trinidad and Tobago be doing more?